Steam turbines

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: May 7, 2023.

We're all used to the idea of boiling water to make tea or coffee, but what if you had to boil water every time you wanted to do anything? What if you had to make steam to charge your iPod, watch TV, or vacuum your carpet? It sounds crazy, yet it's not so far from the truth. Unless you're using renewable energy from something like a solar panel or a wind turbine, virtually every watt of power you consume comes from a power plant that generates electricity from boiling, hissing, rapidly expanding steam! We might not use piston-pushing steam engines to power our world anymore, but we still use their modern equivalents—steam turbines. What are they and how do they work? Let's take a closer look!

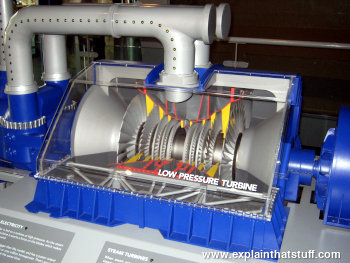

Photo: A one-tenth scale, cutaway model of a steam turbine at Think Tank, the science museum in Birmingham, England. Steam enters from the left through the gray pipe at the top, arriving in the very middle of the turbine and just above it. Then it simultaneously flows in both directions (to the left and the right) through the low-pressure reaction turbine, which drives the electricity generator on the right.

Sponsored links

Contents

Why does steam contain so much energy?

If you've ever burned yourself with steam, you'll know it's incredibly painful—and much more so than an ordinary hot water burn. If water and steam are at the same temperature, why does steam hurt more? Simply because it contains much more energy. To turn 1kg (2.2lb) of water at 100°C (212°F) into 1kg of steam at the same temperature, you need to supply about 2257 kilojoules of energy, or roughly 1000 times as much as an electric kettle or toaster uses in one second. That's an absolutely huge amount of energy! It's what we call the latent heat of vaporization of water: it's the energy you have to supply to move the molecules in the water far enough apart to turn the boiling hot liquid into a hot gas.

So why does steam hurt more? If 100°C boiling water hits your body, it cools down and gives up its heat; that's the energy that burns you. If 100°C steam hits your body, it first turns back to water and then cools down, burning you the same way as the hot water but also giving up the latent heat of vaporization to your body. It's this extra massive dose of heat energy that makes a steam burn so much more serious and painful than a hot water burn. On the positive side, this latent energy "hidden" in steam is what makes it so useful in steam engines and steam turbines!

How does steam provide energy?

If you've ever seen an old-fashioned steam locomotive, you'll have some idea just how powerful steam can be. A steam locomotive is built around a steam engine, a complex machine based on a simple idea: you can burn fuel (coal) to release the energy stored inside it. In a steam engine, coal burns in a furnace and releases heat, which boils water like a kettle and generates high-pressure steam. The steam feeds through a pipe into a cylinder with a tight fitting piston, which moves outward as the steam flows in—a bit like a bicycle pump working in reverse. As the steam expands to fill the cylinder, it cools down, loses pressure, and gives up its energy to the piston. The piston pushes the locomotive's wheels around before returning back into the cylinder so the whole process can be repeated. The steam isn't a source of energy: it's an energy-transporting fluid that helps to convert the energy locked inside coal into mechanical energy that propels a train.

Photo: The power of steam: a restored locomotive running on the Swanage Railway in England. Expanding steam releases energy that drives the engine's pistons. It's pretty obvious that the steam leaving the chimney still contains quite a bit of energy, which is one reason why engines like this are so very inefficient. Steam turbines usefully capture much more of the energy in steam—and are much more efficient.

Steam engines were great: they powered the world throughout the Industrial Revolution from the 18th century right up to the middle of the 20th century. But they were huge, cumbersome, and relatively inefficient. A simple, steam-driven piston and cylinder is delivering energy to the machine it powers only 50 percent of the time (during the power stroke, when the steam is actually pushing it); the rest of the time, it's being pushed back into the cylinder by momentum ready for the next power stroke. Another problem is that pistons and cylinders make back and forth, push-pull, reciprocating motion, when (most of the time) what we'd really prefer is rotary motion—turning a wheel. To make up for these problems, steam engines have elaborately complex cylinders that allow steam in from different directions and heavy levers (cranks and connecting rods) to convert their push-pull reciprocating motion into rotary motion. Wouldn't it be better if we could directly power a wheel with the force of the steam, cutting out the pistons, cylinders, cranks, and all the rest? That's the basic idea behind a steam turbine, an energy converting device perfected by British engineer Sir Charles Parsons in the 1880s.

What is a turbine?

A turbine is a spinning wheel that gets its energy from a gas or liquid moving past it. A windmill or a wind turbine takes energy from the wind, while a waterwheel or water turbine is usually driven by a river flowing over, under, or around it. Now you can't produce energy out of thin air: a basic law of physics called the conservation of energy tells us that a gas or liquid always slows down or changes direction when it flows past a turbine, losing at least as much energy as the turbine gains. Blow on the windmill stuck in your sandcastle and it spins around. What you can't see is that your breath slows down quite dramatically: on the other side of the windmill, the air from your mouth is traveling much slower! Read more in our introduction to turbines.

What is a steam turbine?

Theory of a steam turbine

Artwork: An early steam turbine design developed in 1888 by Swedish engineer Gustav de Laval (1845–1913). It works by directing straight-line jets of high-speed steam at a steel paddle wheel, with reasonable efficiency, so it's an example of an impulse turbine (explained below). Artwork believed to be in the public domain, from The Steam Turbine by Sir Charles Parsons, Cambridge University Press, 1911.

As its name suggests, a steam turbine is powered by the energy in hot, gaseous steam—and works like a cross between a wind turbine and a water turbine. Like a wind turbine, it has spinning blades that turn when steam blows past them; like a water turbine, the blades fit snugly inside a sealed outer container so the steam is constrained and forced past them at speed. Steam turbines use high-pressure steam to turn electricity generators at incredibly high speeds, so they rotate much faster than either wind or water turbines. (A typical power plant steam turbine rotates at 1800–3600 rpm—about 100–200 times faster than the blades spin on a typical wind turbine, which needs to use a gearbox to drive a generator quickly enough to make electricity.) Just like in a steam engine, the steam expands and cools as it flows past a steam turbine's blades, giving up as much as possible of the energy it originally contained. But, unlike in a steam engine, the flow of the steam turns the blades continually: there's no push-pull action or waiting for a piston to return to position in the cylinder because steam is pushing the blades around all the time. A steam turbine is also much more compact than a steam engine: spinning blades allow steam to expand and drive a machine in a much smaller space than a piston-cylinder-crank arrangement would need. That's one reason why steam turbines were quickly adopted for powering ships, where space was very limited.

Parts of a steam turbine

All steam turbines have the same basic parts, though there's a lot of variation in how they're arranged.

Rotor and blades

Photo: Steam turbine blades look a bit like propeller blades but are made from high-performance alloys because the steam flowing past is hot, at high pressure, and traveling fast. Photo of a turbine blade exhibited at Think Tank, the science museum in Birmingham, England.

Running through the center of the turbine is a sturdy axle called the rotor, which is what takes power from the turbine to an electricity generator (or whatever else the turbine is driving). The blades are the most important part of a turbine: their design is crucial in capturing as much energy from the steam as possible and converting it into rotational energy by spinning the rotor round. All turbines have a set of rotating blades attached to the rotor and spin it around as steam hits them. The blades and the rotor are completely enclosed in a very sturdy, alloy steel outer case (one capable of withstanding high pressures and temperatures).

Impulse and reaction turbines

In one type of turbine, the rotating blades are shaped like buckets. High-velocity jets of incoming steam from carefully shaped nozzles kick into the buckets, pushing them around with a series of impulses, and bouncing off to the other side at a similar speed but much-reduced pressure (compared to the incoming jet). This design is called an impulse turbine and it's particularly good at extracting energy from high-pressure steam. (The de Laval turbine illustrated up above is an example.)

In an alternative design called a reaction turbine, there's a second set of stationary blades attached to the inside of the turbine case. These help to speed up and direct the steam onto the rotating blades at just the right angle, before it leaves with reduced temperature and pressure but broadly the same speed as it had when it entered.

In both cases, steam expands and gives up some of its energy as it passes through the turbine. In an ideal world, all the heat and kinetic energy lost by the steam would be gained by the turbine and converted into useful kinetic energy (making it spin around). But, of course, the turbine will heat up somewhat, some steam might leak out, and there are various other reasons why turbines (like all other machines) are never 100 percent efficient.

Photo: Impulse and reaction. 1) This Pelton water wheel is an example of an impulse turbine. It spins as a high-pressure water jet fires into the buckets around the edge from the nozzle on the right. Steam impulse turbines work a bit like this. Photo by Jet Lowe, courtesy of Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record/Historic American Landscapes Survey, US Library of Congress, believed to be in the public domain. 2) A reaction turbine turns when steam hits its curved blades. Photo by Henry Price courtesy of US Department of Energy/National Renewable Energy Laboratory (DOE/NREL).

Other parts

Apart from the rotor and its blades, a turbine also needs some sort of steam inlet (usually a set of nozzles that direct steam onto either the stationary or rotating blades).

Steam turbines also need some form of control mechanism that regulates their speed, so they generate as much or as little power as needed at any particular time. Most steam turbines are in huge power plants driven by enormous furnaces and it's not easy to reduce the amount of heat they produce. On the other hand, the demand (load) on a power plant—how much electricity it needs to make—can vary dramatically and relatively quickly. So steam turbines need to cope with fluctuating output even though their steam input may be relatively constant. The simplest way to regulate the speed is using valves that release some of the steam that would otherwise go through the turbine.

Photo: Huge silver steam pipes feeding turbines at Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith. Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Sponsored links

Practical steam turbines

Multiple stages

"I therefore decided to split up the fall of pressure of the steam into small fractional expansions over a large number of turbines in series so that the velocity of the steam nowhere should be great."

Sir Charles Parsons, The Steam Turbine, 1911.

Photo: The multiple stages in a typical steam turbine. This model is at Think Tank, the science museum in Birmingham, England.

In practice, steam turbines are a bit more complex than we've suggested so far. Instead of a single set of blades on the rotor, there are usually a number of different sets, each one helping to extract a little bit more energy from the steam before it's exhausted. This design is called a compound steam turbine. Each set of blades is called a stage and works by either impulse or reaction, and a typical turbine can have a mixture of impulse and reaction stages, all mounted on the same rotor axle and all turning the generator at the same time. Often the impulse stages come first and extract energy from the steam when it's at high pressure; the reaction stages come later and remove extra energy from the steam when it's expanded to a bigger volume and lower pressure using longer, bigger blades. The multi-stage approach, invented by Charles Parsons, means each stage is slowing or reducing the pressure of the steam by only a relatively small amount, which reduces the forces on the blades (an important consideration for a machine that may have to run for years without stopping) and greatly improves the turbine's overall power output.

Photo: Multiple stages (closeup): Zooming in on the photo above, you can see how each stage is bigger than the previous one: bigger in diameter, more widely spaced, with bigger blades set at greater angles that have wider openings in between them. This allows the steam to expand gradually on its journey through the turbine, which is how it gives up its energy. You can see the same thing even more clearly if you check out this wonderful photo of an old dual-flow Siemens steam turbine from a nuclear plant.

Artwork: The Curtis turbine, designed in 1896 by Charles G. Curtis, is a compound impulse turbine. In effect, it's a cross between a simple de Laval impulse turbine and a multi-stage Parsons reaction turbine. Steam enters through nozzles at the top (yellow) then passes between a series of moving (blue) and stationary (red) blades before exiting at the bottom. It hits each blade and bounces off—just like in a simple impulse turbine. Artwork believed to be in the public domain, from The Steam Turbine by Sir Charles Parsons, Cambridge University Press, 1911.

Condensing and noncondensing

Turbines also vary in how they cool the steam that passes through them. Condensing turbines (used in large power plants to generate electricity) turn the steam at least partly to water using condensers and giant concrete cooling towers. This allows the steam to expand more and helps the turbine extract the maximum energy from it, making the electricity generating process much more efficient. A large supply of cold water is needed to condense the steam, and that's why electricity plants with condensing turbines are often built next to large rivers. Noncondensing turbines don't cool the steam so much, and use the heat remaining in it to make hot water in a system known as combined heat and power (CHP or cogeneration).

Photo: Cooling towers like these help a steam turbine condense steam to extract more energy in a heating-cooling process known as the Rankine cycle. If you're uncertain why we need cooling towers, check out The Energy Cost of Heat by David MacKay, an extract from his excellent book Sustainable Energy: Without Hot Air. These are the towers at Didcot power station near Oxford, England.

Photo: Cooling towers are completely open at the base to let huge draughts of air enter. I photographed these towers at Ratcliffe on Soar power plant near Nottingham, England.

Practical steam turbines come in all shapes and sizes and produce power ranging from one or two megawatts (roughly the same output as a single wind turbine) up to 1,000 megawatts or more (the output from a large power plant, equivalent to 500–1000 wind turbines working at full capacity). In the biggest turbines, in large fossil-fuel power plants, the steam pressure can be as high as 20–30MPa (3000–4000 psi or about 200–270 times atmospheric pressure). A small, 10 megawatt steam turbine is roughly the same size as a Greyhound bus (a large single-deck passenger coach).