Iron and steel

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: May 2, 2022.

Think of the greatest structures of the 19th century—the Eiffel Tower, the Capitol, the Statue of Liberty—and you'll be thinking of iron. [1] The fourth most common element in Earth's crust, iron has been in widespread use now for about 6000 years. [2] Hugely versatile, and one of the strongest and cheapest metals, it became an important building block of the Industrial Revolution, but it's also an essential element in plant and animal life. Combined with varying (but tiny) amounts of carbon, iron makes a much stronger material called steel, used in a huge range of human-made objects, from cutlery to warships, skyscrapers, and space rockets. Let's take a closer look at these two superb materials and find out what makes them so popular!

Photo: The world's first cast-iron bridge, after which the village of Ironbridge in Shropshire, England was named. It was built across the River Severn by Abraham Darby III in 1779 using some 384 tons of iron. You can read more about its history and construction on the official Ironbridge website. Photo by Jason Smith courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Sponsored links

Contents

What is iron like?

Photo: A sample of iron from a meteorite (next to a pen for scale). From the mineral collection of Brigham Young University Department of Geology, Provo, Utah. Photograph by Andrew Silver courtesy of US Geological Survey Photographic Library.

You might think of iron as a hard, strong metal tough enough to support bridges and buildings, but that's not pure iron. What we have there is alloys of iron (iron combined with carbon and other elements), which we'll explain in more detail in a moment. Pure iron is a different matter altogether. Consider its physical properties (how it behaves by itself) and its chemical properties (how it combines and reacts with other elements and compounds).

Physical properties

Pure iron is a silvery-white metal that's easy to work and shape and it's just soft enough to cut through (with quite a bit of difficulty) using a knife. You can hammer iron into sheets and draw it into wires. Like most metals, iron conducts electricity and heat very well and it's very easy to magnetize.

Chemical properties

The reason we so rarely see pure iron is that it combines readily with oxygen (from the air). Indeed, iron's major drawback as a construction material is that it reacts with moist air (in a process called corrosion) to form the flaky, reddish-brown oxide we call rust. Iron reacts in lots of other ways too—with elements ranging from carbon, sulfur, and silicon to halogens such as chlorine.

Broadly, iron's compounds can be divided into two groups known as ferrous and ferric (the old names) or iron (II) and iron (III); you can always substitute "iron(II)" for "ferrous" and "iron(III)" for "ferric" in compound names.

- In iron (II) compounds, iron has a valency (chemical combining ability) of +2. Examples include iron(II) oxide (FeO), a pigment (coloring chemical); iron (II) chloride (FeCl2), used in medicine as "tincture of iron"; and an important dyeing chemical called iron (II) sulfate (FeSO4).

- In iron (III)

compounds, iron's valency is +3. Examples include iron (III) oxide

(Fe2O3), used as

the magnetic material in things like cassette tapes

and computer hard drives and also as a paint pigment; and iron (III)

chloride (FeCl3), used to manufacture many

industrial chemicals.

Photo: Iron in action: Chances are you're using magnetic iron (III) oxide right this minute in your computer's hard drive.

- Sometimes iron (II) and iron (III) are present in the same compound. A paint pigment called Prussian blue is actually a complex compound of iron (II), iron (III), and cyanide with the chemical formula Fe4[Fe(CN)6]3.

Where does iron come from?

Photo: Iron is essential for a healthy diet, which is why it's packed into many breakfast cereals. Here's a great little experiment from Scientific American to extract the iron from your cornflakes.

Iron is the fourth most common element in Earth's crust (after oxygen, silicon, and aluminum), and the second most common metal (after aluminum), but because it reacts so readily with oxygen it's never mined in its pure form (though meteorites are occasionally discovered that contain samples of pure iron). Like aluminum, most iron "locked" inside Earth exists in the form of oxides (compounds of iron and oxygen). Iron oxides exist in seven main ores (raw, rocky minerals mined from Earth):

- Hematite (the most plentiful)

- Limonite (also called brown ore or bog iron)

- Goethite

- Magnetite (black ore; the magnetic type of iron oxide, also called lodestone)

- Pyrite

- Siderite

- Taconite (a combination of hematite and magnetite).

Different ores contain different amounts of iron. Hematite and magnetite have about 70 percent iron, limonite has about 60 percent, pyrite and siderite have 50 percent, while taconite has only 30 percent. Using a combination of both deep mining (under the ground) and opencast mining (on the surface), the world produces approximately 1000 million tons of iron ore each year, with China responsible for just over half of it.

Which countries produce the world's iron? As you can see, China utterly dominates as the source of about two thirds of the iron we use. Chart shows estimated figures for pig iron for 2021. In the United States, three companies currently produce pig iron in 11 different locations. Source: US Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2022.

Types of iron

Pure iron is too soft and reactive to be of much real use, so most of the "iron" we tend to use for everyday purposes is actually in the form of iron alloys: iron mixed with other elements (especially carbon) to make stronger, more resilient forms of the metal including steel. Broadly speaking, steel is an alloy of iron that contains up to about 2 percent carbon, while other forms of iron contain about 2–4 percent carbon. In fact, there are thousands of different kinds of iron and steel, all containing slightly different amounts of other alloying elements.

Pig iron

Basic raw iron is called pig iron because it's produced in the form of chunky molded blocks known as pigs. Pig iron is made by heating an iron ore (rich in iron oxide) in a blast furnace: an enormous industrial fireplace, shaped like a cylinder, into which huge drafts of hot air are introduced in regular "blasts". Blast furnaces are often spectacularly huge: some are 30–60m (100–200ft) high, hold dozens of trucks worth of raw materials, and often operate continuously for years at a time without being switched off or cooled down. Inside the furnace, the iron ore reacts chemically with coke (a carbon-rich form of coal) and limestone. The coke "steals" the oxygen from the iron oxide (in a chemical process called reduction), leaving behind a relatively pure liquid iron, while the limestone helps to remove the other parts of the rocky ore (including clay, sand, and small stones), which form a waste slurry known as slag. The iron made in a blast furnace is an alloy containing about 90–95 percent iron, 3–4 percent carbon, and traces of other elements such as silicon, manganese, and phosphorus, depending on the ore used. Pig iron is much harder than 100 percent pure iron, but still too weak for most everyday purposes.

Cast iron

Photo: The cast-iron dome of the US Capitol. Credit: The George F. Landegger Collection of District of Columbia Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

One of the world's most famous iron buildings, the Capitol in Washington, DC has a dome made of 4,041,146kg (8,909,200 pounds) of cast iron. Cast iron is simply liquid iron that has been cast: poured into a mold and allowed to cool and harden to form a finished structural shape, such as a pipe, a gear, or a big girder for an iron bridge. Pig iron is actually a very basic form of cast iron, but it's molded only very crudely because it's typically melted down to make steel. The high carbon content of cast iron (about the same as pig iron—roughly 2–4 percent) makes it extremely hard and brittle: large crystals of carbon embedded in cast iron stop the crystals of iron from moving about. Cast iron has two big drawbacks: first, because it's hard and brittle, it's virtually impossible to shape, even when heated; second, it rusts relatively easily. It's worth noting that there are actually several different types of cast iron, including white and gray cast irons (named for the coloring of the finished product caused by the way the carbon inside it behaves).

Wrought iron

Cast iron assumes its finished shape the moment the liquid iron alloy cools down in the mold. Wrought iron is a very different material made by mixing liquid iron with some slag (leftover waste). The result is an iron alloy with a much lower carbon content. Wrought iron is softer than cast iron and much less tough, so you can heat it up to shape it relatively easily, and it's also much less prone to rusting. However, relatively little wrought iron is now produced commercially, since most of the objects originally produced from it are now made from steel, which is both cheaper and generally of more consistent quality. Wrought iron is what people used to use before they really mastered making steel in large quantities in the mid-19th century.

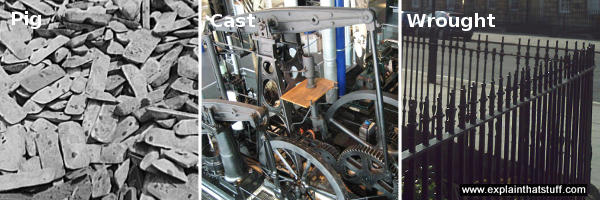

Photo: Three types of iron. Left: Pig iron is the raw material used to make other forms of iron and steel. Each of these iron pieces is one pig. Middle: Cast iron was used for strong, structural components like bits of engines and bridges before steel became popular. Right: Wrought iron is a softer iron once widely used to make everyday things like street railings. Today, wrought iron is more of a marketing description for what is actually mild steel (low-carbon steel), which is easily worked and shaped. Left photo by Alfred T. Palmer courtesy of US Library of Congress. Middle and right photos by explainthatstuff.com.

Types of steel

Strictly speaking, steel is just another type of iron alloy, but it has a much lower carbon content than cast iron and roughly the same (or sometimes slightly more) carbon than wrought iron, and other metals are often added to give it extra properties. [3] Steel is such an amazingly useful material that we tend to talk about it as though it were a metal in its own right—a kind of sleeker, more modern "son of iron" that's taken over the family firm! It's important to remember two things, however. First, steel is still essentially (and overwhelmingly) made from iron. Second, there are literally thousands of different types of steel, many of them precisely designed by materials scientists to perform a particular job under very exacting conditions. When we talk about "steel", we usually mean "steels"; broadly speaking, steels fall into four groups: carbon steels, alloy steels, tool steels, and stainless steels. These names can be confusing, because all alloy steels contain carbon (as do all other steels), all carbon steels are also alloys, and both tool steels and stainless steels are alloys too.

Chart: Which countries produce the world's raw steel? Again, China utterly dominates. Approximately 1.9 billion metric tons of steel are made worldwide each year, and half of it comes from China. This chart shows estimated worldwide raw steel production figures for the years 2018 (inner ring)–2021 (outer ring). In the United States, there were 101 "minimill" steel plants operating at the start of 2021 (down from 110 in 2018) making a total of about 106 million tons of steel (slightly down from 114 million tons in 2015). Indiana (27 percent), Ohio (11 percent), Pennsylvania (5 percent), Illinois and Texas (4 percent each) and Michigan (3 percent) together produce about half of all US steel. Source: US Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2022.

Carbon steels

The vast majority of steel produced each day (around 80–90 percent) is what we call carbon steel, though it contains only a tiny amount of carbon—sometimes much less than 1 percent. In other words, carbon steel is just basic, ordinary steel. Steels with about 1–2 percent carbon are called (not surprisingly) high-carbon steels and, like cast-iron, they tend to be hard and brittle; steels with less than 1 percent carbon are known as low-carbon steels ("mild steels") and like wrought iron, are softer and easier to shape. A huge range of different everyday items are made with carbon steels, from car bodies and warship hulls to steel cans and engine parts.

Alloy steels

As well as iron and carbon, alloy steels contain one or more other elements, such as chromium, copper, manganese, nickel, silicon, or vanadium. In alloy steels, it's these extra elements that make the difference and provide some important additional feature or improved property compared to ordinary carbon steels. Alloy steels are generally stronger, harder, tougher, and more durable than carbon steels.

Tool steels

Tool steels are especially hard alloy steels used to make tools, dies, and machine parts. They're made from iron and carbon with added elements such as nickel, molybdenum, or tungsten to give extra hardness and resistance to wear. Tool steels are also toughened up by a process called tempering, in which steel is first heated to a high temperature, then cooled very quickly, then heated again to a lower temperature.

Stainless steels

The steel you probably see most often is stainless steel—used in household cutlery, scissors, and medical instruments. Stainless steels contain a high proportion of chromium and nickel, are very resistant to corrosion and other chemical reactions, and are easy to clean, polish, and sterilize. They're corrosion-proof because the chromium atoms react with oxygen in the air to form a kind of protective outer skin that stops oxygen and water from attacking the vulnerable iron atoms inside.

Sponsored links

Making steel

There are three main stages involved in making a steel product. First, you make the steel from iron. Second, you treat the steel to improve its properties (perhaps by tempering it or plating it with another metal). Finally, you roll or otherwise shape the steel into the finished product.

Making steel from iron

Photo: Making steel from iron with a Bessemer converter. It turns iron into steel with help from oxygen in the air. Photo by Alfred T. Palmer courtesy of US Library of Congress.

Most steel is made from pig iron (remember: that's an iron alloy containing up to 4 percent carbon) by one of several different processes designed to remove some of the carbon and (optionally) substitute one or more other elements. The three main steelmaking processes are:

- Basic oxygen process (BOP): The steel is made in a giant egg-shaped container, open at the top, called a basic oxygen furnace, which is similar to an ordinary blast furnace, only it can rotate to one side to pour off the finished metal. The air draft used in a blast furnace is replaced with an injection of pure oxygen through a pipe called a lance. The basic idea is based on the Bessemer process developed by Sir Henry Bessemer in the 1850s.

- Open-hearth process (also called the regenerative open hearth): A bit like a giant fireplace in which pig iron, scrap steel, and iron ore are burned with limestone until they fuse together. More pig iron is added, the unwanted carbon combines with oxygen, the impurities are removed as slag and the iron turns to molten steel. Skilled workers sample the steel and continue the process until the iron has exactly the right carbon content to make a particular type of steel.

- Electric-furnace process: You don't cook your dinner with an open fire, so why make steel in such a primitive way? That's the thinking behind the electric furnace, which uses electric arcs (effectively giant sparks) to melt pig iron or scrap steel. Since they're much more controllable, electric furnaces are generally used to make higher-specification alloy, carbon, and tool steels.

Photo: Making steel for weaponry with the three-ton electric arc furnace at Rock Island Arsenal. Photo by Tony Lopez courtesy of Defense Imagery.

Making steel products

Liquid steel made by one of these processes is cast into huge bars called ingots, each of which weighs anything from a couple of tons (in typical steel plants) to hundreds of tons (in really big plants making giant steel objects). The ingots are rolled and pressed to make three types of basic steel "building blocks" known as blooms (giant bars with square ends), slabs (blooms with rectangular ends), and billets (longer than blooms but with smaller square ends).

These blocks are then shaped and worked to make all kinds of final

steel products. The

basic shaping process usually involves hot rolling

(for

example, reheating

blooms and then rolling them over and over again to make them

thinner). Girders are made by rolling steel then forcing it through

dies or milling machines to make such things as beams for buildings

and railroad tracks. Rollers that are very close together can be used

to squeeze steel into extremely thin sheets. Pipes are made by wrapping

sheets

round into circles then forcing the two edges together so they fuse

under pressure where they join.

Shaped steel can be further treated in all kinds of ways. For example, "tins" for food containers (which are mostly steel) are made by electroplating steel sheets with molten tin using the process of electrolysis (the reverse of the electro-chemical process that happens in batteries). Steel that needs to be especially resistant to weathering can be galvanized (dipped into a hot bath of molten zinc so it acquires an overall protective coating).