Valves

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: August 4, 2023.

What's the world's favorite form of transportation? The car? The bicycle? The jet airplane? If I had to hazard a guess, I'd pick none of these things. Instead, I'd opt for the humble pipeline. You might not notice pipes, but they're transporting vast amounts of fluid (liquid and gas) around the world quietly and efficiently, day in and day out. To work efficiently, pipes need a way of regulating how much fluid can pass through them; they also need a way of switching the flow off completely. That's the job that valves do: valves are like mechanical switches that can turn pipes on and off or raise or lower the amount of fluid flowing through them. Let's take a closer look at how they work!

Photo: This stop valve is manually operated: you open and close it by turning the wheel. A wheel like this makes a valve easier to open because it multiplies the force you apply at the rim to produce a bigger and more useful force at the center. If you're not sure why, take a look at our article on tools and machines. Photo by Brian Sloan courtesy of US Navy and DVIDS.

Sponsored links

Contents

What are valves?

A valve is a mechanical device that blocks a pipe either partially or completely to change the amount of fluid that passes through it. When you turn on a faucet (tap) to brush your teeth, you're opening a valve that allows pressurized water to escape from a pipe. Similarly, when you flush the toilet, you open two valves: one (the siphon) that allows water to escape to empty the pan and another (called a ball valve or ballcock) that admits more water into the tank ready for the next flush.

Photo: Valves come in all sizes. Some are tiny, like this poppet valve, which slides up and down on top of a drinks bottle to let the water in and out when you pull or push it with your teeth.

Valves regulate gases as well as liquids. If you have a gas cooktop (hob) on your stove, the controls that turn the gas up or down are valves. When you turn up the heat, you're opening a valve that allows more gas to flow in through the pipe. More gas burns with a bigger flame so you get more heat.

Valves are pretty much guaranteed to be in any machine that use liquids or gases. There's a valve in your clothes washer that turns the water supply on or off each time the drum rinses out. There are also valves in the cylinders of your car engine, opening and closing several times a second to admit air and fuel and to allow burned exhaust gases to escape.

It's not just machines that use valves. Your body has some pretty important valves inside your heart that allow it to pump blood to your lungs (where it picks up oxygen) and then around your body.

Photo: Valves big and small. 1) This 7.3-m (24-ft) diameter butterfly valve from a wind tunnel dwarfs the man standing next to it! Photo by courtesy NASA on the Commons 2) This much smaller butterfly valve works the same way, swiveling open in the center to let air through a pipe. Photo by courtesy of NASA Glenn Research Center (NASA-GRC) and Internet Archive.

How are valves made?

Valves are usually made of metal or plastic and they have several different parts. The outer part is called the seat and it often has a solid metal outer casing and a soft inner rubber or plastic seal so the valve makes a closure that's absolutely tight. The inner part of the valve, which opens and closes, is called the body and fits into the seat when the valve is closed. There's also some form of mechanism for opening and closing the valve—either a manual lever or wheel (as in a faucet or a stop cock) or an automated mechanism (as in a car engine or steam engine).

Photo: Shutting off the water with a sturdy brass isolation valve. Turning this lever through ninety degrees closes a ball valve in the middle of the pipe, cutting off the water flowing through. Most homes have valves like this on the incoming cold water "feed" and the pipes leading into and out from the water tanks. Isolation valves are very useful during an emergency (such as a burst water pipe) or for carrying out routine maintenance. Once the valve is closed, you can safely carry out repairs without the fluid all flooding out.

It's often critically important for valves that are switched off to allow absolutely no escape of liquid or gas through a pipe to avoid accidents, explosions, pollution, or the loss of valuable chemicals (even a dripping faucet can be expensive if your water is metered). That's why the seal on a valve needs to be perfectly secure and a valve that's turned off must be tightly closed. Turning off a high-pressure flow of liquid or gas by obstructing it with a valve is physically hard work: in other words, you need to use a lot of force to do it. That's why some valves are operated by levers (like the one photographed here, but some can be much longer to give you more turning force) or large wheels (as in the top photo in this article). If really big valves require too much force for a human to supply, they're operated by hydraulic rams.

Choosing the right material

Not all valves are big, mighty, industrial-strength things made of metal. Look carefully at food containers in your kitchen and you'll find quite a few have valves in them. Water bottles (like the one I pictured above) often have poppet valves instead of screw caps. The food jar top I've photographed below is another really ingenious example of a valve, made from a springy elastomer (in practice, an elastic, synthetic, silicone rubber). It seals a food dispensing jar that normally sits upside down, so, in theory, the food could just dribble out onto the table beneath! This ingenious valve is what stops it. The rubbery material has four slits in it to let the food through, but it's also quite firm, so it opens only when you squeeze the jar. The pressure you supply when you squeeze forces the food through the four slits, which pop open. When you release the pressure, the elasticity of the valve makes the slits pop back down and the seal the jar up again. It's so simple and mundane that you've probably never even noticed it, yet it's an ingenious bit of engineering that relies on very careful selection of exactly the right material.

Photo: An elastomeric food-sealing valve. Left: Looking from below at the sealed valve. Middle: Looking from above at the same sealed valve. Right: Looking from above with my finger pushing up to reveal how the self-sealing slit mechanism works. (If you're interested, I believe this is a SimpliSqueeze® slit valve made by Aptar, and you can read all the technical details of how it works in their US10287066B2: Dispensing valve.)

And choosing materials for valves isn't just a matter of thinking how they'll function during their lifetime, but what happens to them after that. With food packaging, for example, recycling is an increasingly important consideration. Take the little valves you find on coffee bags. After coffee is roasted and stuffed into bags, it might have to sit on a store shelf for anything up to a year, during which time it continues to give off carbon dioxide gas. Without a valve on the bag, it would puff up and potentially burst in the shop (or your kitchen), hurling coffee all over the place. So coffee bags have these ingenious one-way "degassing" valves on them made of membranes that open when the pressure builds up inside. That's why you can "wake up and smell the coffee" without actually opening the bag. When air tries to push in from outside, it flattens the membrane and seals the bag tight. So far so good, but what about recycling? If you start putting complicated plastic valves on bags, it makes the bags far harder to recycle. What's the answer? Manufacturers are now making coffee bags and valves entirely from compostable bioplastics to eliminate the waste disposal problem.

Photo: How coffee valves work. Top row: Left: A typical valve on the inside of a bag of coffee. Middle: This compostable bioplastic valve (made by the Swiss Wipf company) has a fixed outer seat (black) and an inner body (red) with a gas vent. Right: Take it apart and you'll find it also has a plastic membrane inside (blue). The illustration below shows how these three parts work together. The membrane flexes up to let CO2 escape, then flattens back down to stop air and water vapor getting in.

Sponsored links

Types of valves

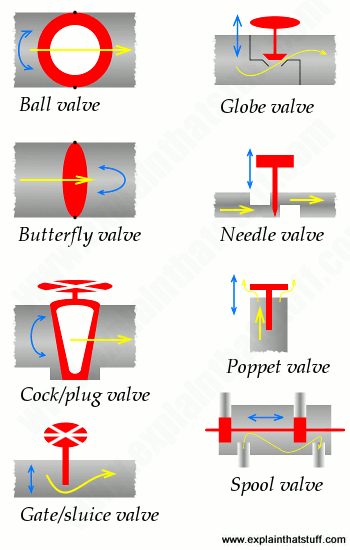

Artwork: Eight common types of valves, greatly simplified. Color key: the grey part is the pipe through which fluid flows; the red part is the valve and its handle or control; the blue arrows show how the valve moves or swivels; and the yellow line shows which way the fluid moves when the valve is open.

The many different types of valves all have different names. The most common ones are the butterfly, cock or plug, gate, globe, needle, poppet, and spool:

- Ball: In a ball valve, a hollowed-out sphere (the ball) sits tightly inside a pipe, completely blocking the fluid flow. When you turn the handle, it makes the ball swivel through ninety degrees, allowing the fluid to flow through the middle of it.

- Butterfly: A butterfly valve is a disk that sits in the middle of a pipe and swivels sideways (to admit fluid) or upright (to block the flow completely).

- Cock or plug: In a cock or plug valve, the flow is blocked by a cone-shaped plug that moves aside when you turn a wheel or handle.

- Gate or sluice: Gate valves open and close pipes by lowering metal gates across them. Most valves of this kind are designed to be either fully open or fully closed and may not function properly when they are only part-way open. Water supply pipes use valves like this.

- Globe: Water faucets (taps) are examples of globe valves. When you turn the handle, you screw a valve up or down and this allows pressurized water to flow up through a pipe and out through the spout below. Unlike a gate or sluice, a valve like this can be set to allow more or less fluid through it.

- Needle: A needle valve uses a long, sliding needle to regulate fluid flow precisely in machines like car engine carburetors and central-heating systems.

- Poppet: The valves in car engine cylinders are poppets. This type of valve is like a lid sitting on top of a pipe. Every so often, the lid lifts up to release or admit liquid or gas.

- Spool: Spool valves regulate the flow of fluid in hydraulic systems. Valves like this slide back and forward to make fluid flow in either one direction or another around a circuit of pipes.