Streaming media

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: August 1, 2023.

A decade or two ago, the telephone wire heading into your home was a quaint way to chat with your family and friends when you couldn't speak to them in person. The basic idea hadn't changed much since the 1870s, when Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922) and others pioneered telephone technology. But in the 21st century, people have started to see telephone lines a different way: now they're broadband Internet connections, piping music downloads, YouTube videos, news, and information—as well as telephone calls—into our homes 24 hours a day. Streaming media (a way of playing files as they download) has been a central part of this information revolution. What is it, exactly, and how does it work? Let's take a closer look!

Photo: TV and movies as many of us now see them: streamed through a laptop or cellphone screen.

Sponsored links

Contents

What is streaming media?

If a picture is a worth a thousand words, a moving picture is worth a million. But how do you cram all that information down a telephone? The trouble is that a couple of copper wires—the basic technology behind our home phone lines—cannot, ordinarily carry information quickly enough to bring things like radio and TV into our homes. If you've ever watched a fax machine chugging along, sending or receiving a printed document at a grindingly slow speed, you'll know just how slow telephone lines can be at carrying anything other than a person's voice (the only job they were ever designed to do).

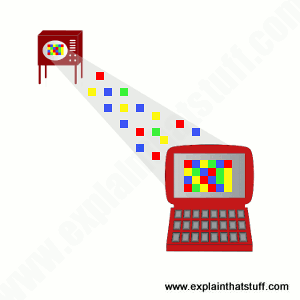

Artwork: The concept of streaming media: transmitting a movie, TV program, or other video across the Internet for viewing on a PC or mobile device.

In the days when most people had dial-up Internet connections (where you make a connection to your Internet Service Provider using a modem to enable what is essentially just a normal telephone call), slow speeds were a major limitation on what could be done online. If you wanted to listen to an MP3 music track (typically about 5 megabytes in size), you could spend half an hour waiting for the entire file to download onto your hard drive, then open it up and play it back. Video files (more likely to be 50 megabytes) would take several hours to download this way, so they were not generally available on the Net. In those days, it was impossible to listen to a music or movie file of any size without a long and tedious wait. The problem was essentially a matter of bandwidth: the speed of an Internet connection (how quickly it can download information) sets a limit to how quickly you can transfer a file.

In the mid-1990s, in the early days of the Web, Rob Glaser and his Real company (originally called Progressive Networks) pioneered streaming media as the solution to this problem. The basic idea is simple. Suppose you want to watch a large video file on your PC. You install a media player (a streaming-media-playing program) on your computer that plays the file while it downloads. So it downloads maybe the first 10 seconds of the file, stores or buffers it, then immediately starts to play it. As the media player starts playing the first part of the file, it's also downloading the next 10 seconds ready for when you come to that bit. The media player never actually stores more than a little bit of the entire file: once it's played part of the file, it deletes it to make way for the next bit. If the media player can download the file as fast as you're watching or listening to it, you'll see no interruptions; if there are delays in downloading for any reason, there will be occasional pauses while the player downloads and "buffers" the next bit of the file.

Photo: Streaming media as it used to be. This is an early version of RealPlayer (the program that kick-started the streaming media revolution) playing here over a 56 Kbps dial-up Internet connection. The status bar at the bottom shows the radio station is being played at 44.1 Kbps (over 44,000 binary digits per second), which is well within the limits of the connection. The trick with streaming media is for the player to adapt to the limits of your Internet connection to avoid excessive buffering. Although modern fiber broadband connections have about 1000 times the bandwidth of dialup, buffering can still be an issue because people download much bigger files (HD movies) these days.

Downloading and streaming compared

Before we go any further, we need to know more about how the Internet works.

Data (computerized information) moves efficiently across the Internet by being broken up into little bits known as packets. Each packet is independently addressed and travels separately, and different packets can travel by very different routes. Imagine yourself wanting to send a really heavy textbook to a friend in another country. Instead of sending the entire book, you tear it into separate pages, put each one in its own envelope with a separate stamp and address, and mail all those envelopes one after another. Your friend may receive them at slightly different times, in the wrong order, but she can easily reassemble them into the book. Why would you mail a book in such an odd way? It turns out the Internet works best this way with everything broken into small, similar-sized chunks. (We have a whole article about how the Internet works that explains all this in more detail.)

When you download a file in the traditional way, you're effectively asking another computer (a server that sends out files to many different people) to send you zillions of packets one after another and you have to wait for all of them to arrive before you can do anything with any of them. With streaming, you start to use the packets as soon as enough of them have arrived. That's the essential difference. You can think of streaming as playing during downloading, but in fact the two things are different in all sorts of ways:

- Speed

- Downloading: Unpredictable: Download time is unrelated to playing time. A music album could download in 5 seconds, 5 minutes, or 5 hours depending on its size, your net connection, and web traffic.

- Streaming: Real time: Generally, a 1 hour video will stream in roughly 1 hour (though there may be occasional delays caused by buffering); unlike downloading, streaming media can be used for "live-live" transmission of events as they happen (also known as webcasting).

- Quality

- Downloading: Uses traditional Internet packet communication (technically known as TCP/IP) with a system that automatically corrects errors. Any lost or damaged "packets" (downloaded chunks of data) are retransmitted. The file you eventually receive on your computer is an exact copy of the file that was on the server.

- Streaming: Packet losses are ignored (lost and damaged packets are not resent), but that doesn't usually matter because digitally streamed video and audio is converted back into analog format before we watch it or listen to it. Any packets lost during streaming simply add "surface noise" to an audio stream or degrade the picture quality of a video (for example, with excessive pixelation (where the picture disappears into square blocks).

- File type

- Downloading: A download is a single file with all the relevant data packaged together. So if you're downloading a movie, everything is packaged into a single movie file with a filetype something like MPEG4.

- Streaming: If you stream a movie, each different part of the movie (sound, video, subtitles, or whatever) is transmitted as a separate stream. The movie player reassembles and synchronizes the streams as they arrive at your computer. In terms of bandwidth, these multiple streams are additive: if you're back in the Dark Ages with a slow 56 Kbps dial-up modem, you could happily watch a 20 Kbps audio stream and a 30 Kbps video stream together, but any extra streams would cause periodic pauses and buffering.

- Servers

- Downloading: Downloads work through traditional web-serving methods (technically known as the HTTP and FTP protocols) with any conventional web server. The same version of each file is served to everyone.

- Streaming: Streams use RTSP (real-time streaming protocol) and need to run on a server specially geared for streaming. When you go to a web page that offers streaming media, you're generally redirected to a separate streaming server. There are typically different versions of each file that have been optimized for different connection speeds (for example, a low-quality version for dial-up and a high-quality version for broadband); in practice, different files are served to different people.

- Encoding/decoding

- Downloading: Files can be instantly uploaded to a server for immediate downloading.

- Streaming: Files have to be compressed (perhaps using smaller video frames or fewer frames per second) and then encoded (turned into discrete, digital packets) before they can be streamed. People watching or listening to streamed files have to have appropriate decoding files installed on their computers (known as codecs) for turning encoded, computerized, digital files back into analog sounds and pictures that human ears and eyes can process. In practice, that means you need a plugin in your web-browser to handle whatever streaming media files you want to receive (and you'll need separate plugins for QuickTime, RealPlayer, and so on).

- Multiple users

- Downloading: The more people ("clients") download a file at the same time, the harder the server has to work, the slower it works for each client, and the longer it takes you to download—irrespective of how fast an Internet connection you have. (BitTorrent offers one solution to this problem.)

- Streaming: In traditional streaming (unicasting), each client takes a separate stream from the server—necessarily, because different people will start streaming the same video or audio program at different times. Multicasting is a more efficient kind of streaming that allows a streaming server to produce a single stream that many people can watch or listen to simultaneously—for example, if lots of people are watching a football game live online at the same time. Some media players automatically use multicasting when they can.

- Standards

- Downloading: Downloaded files tend to be in standard formats (such as MP3) that play easily on any computer or operating system.

- Streaming: There are three rival, proprietary streaming systems (more formally known as architectures—RealPlayer, Apple QuickTime, and Microsoft Windows Media Player), and though they're much more compatible than they used to be, it's not always possible to play files designed for one player on the others.

- Copyright

- Downloading: Downloaded files are, by definition, copied onto the viewer's computer. They're easy to email, post on other websites, and repackage or resell—causing major copyright issues.

- Streaming: Streamed files are downloaded a little bit at a time and deleted as soon as they're played. In theory, nothing remains on the viewer's computer so there are fewer copyright issues. (In practice, programs have been written that can record streamed files.)

Examples of streaming media

Photo: Netflix, the world's biggest and best-known streaming service, now has close to 200 million subscribers worldwide. It streams movies and TV programs down your Internet connection in "real time." That means programs play at the same rate they download, and each program takes roughly the same time to watch via streaming as it would if viewed live on your television.

Genuine streaming

Photo: Genuine streaming: YouTube uses a type of streaming that continually adapts to the speed and quality of your Internet connection; previously it used progressive downloading (described below).

Netflix and YouTube currently use what's called adaptive bitrate streaming, which constantly adjusts ("adapts") the stream rate to the quality of your Internet connection and the performance of your computer. It's based on the ordinary method of sending packet data across the Internet (hypertext transfer protocol, HTTP), so it's better suited to sending data over the Net than older streaming "protocols" such as RTP (real-time protocol), used by early streaming players such as Real (described in the box below). One advantage is that it can cope with mobile networks that may switch back and forth between high (5G and 4G) and slower (3G) speeds as you move around.

Most Internet radio stations use either this kind of adaptive (HTTP) streaming or older-style (RTP) streaming, where programs are downloaded and played simultaneously in your web browser, with a dedicated app, or with a program like RealPlayer, Apple's QuickTime, or the Microsoft Windows Media Player. With a decent broadband connection, you can enjoy audio quality that's not far off the quality you get from a downloaded MP3 sound file (though, as we discuss in our article on MP3, that's never quite as good as you'd get from a CD). As Internet connections have become faster, and more people have broadband, it's become possible to watch videos and TV programs this way too, though unless you stream in high definition over a really fast broadband line, quality is still short of what you'd get from watching TV or a DVD. That's one reason why online movie stories still sometimes use downloads instead of streaming.

Pseudo-streaming: progressive downloading

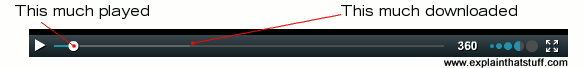

Not all websites that appear to stream video work by streaming. Some actually use an alternative approach called progressive downloading (fast-start streaming), which is like a cross between conventional downloading and streaming (YouTube used to work this way until a few years ago). It's popular because it's often quicker and easier to implement than genuine streaming. A large chunk (and sometimes all) of the file you're watching downloads into your web browser's cache (its internal working memory buffer) and your browser plays it simultaneously. Unlike with a truly streamed video, you can't always skip forward: generally you have to wait for the file to download to the point you want to see. Another key difference is that the file remains in your browser cache even when you've finished watching. You can tell when a website is working by progressive downloading because the video window will show two separate indicators on a progress bar, like the one below: one shows you how much of the file has downloaded, while the other shows how much you've played. Until recently, almost all progressive downloading used Macromedia Flash files (with SWF or FLV extensions), that are served from a conventional web server and played on a Flash plugin installed in your browser. Following the arrival of HTML5, modern browsers (including the slimmed-down ones on smartphones) can now do this themselves without using Flash at all.

Photo: A progressive downloading progress bar. When you see this, you're not actually streaming a video—you're playing it as you download the entire thing. If you know how to look in your browser cache, you'll probably find the file is sitting in there somewhere after you've played it (look for a very big file or one with a very new date and time, but don't expect to find a meaningful filename or extension).