Radio

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: May 20, 2022.

Free music, news, and chat wherever you go! Until the Internet came along, nothing could rival the reach of radio—not even television. A radio is a box filled with electronic components that catches radio waves sailing through the air, a bit like a baseball catcher's mitt, and converts them back into sounds your ears can hear. Radio was first developed in the late-19th century and reached the height of its popularity several decades later. Although radio broadcasting is not quite as popular as it once was, the basic idea of wireless communication remains hugely important: in the last few years, radio has become the heart of new technologies such as wireless Internet, cellphones (mobile phones), and RFID (radio frequency identification) chips. Meanwhile, radio itself has recently gained a new lease of life with the arrival of better-quality digital radio sets.

Photo: An antenna to catch waves, some electronics to turn them back into sounds, and a loudspeaker so you can hear them—that's pretty much all there is to a basic radio receiver like this. What's inside the case? Check out the photo in the box below!

Sponsored links

Contents

What is radio?

You might think "radio" is a gadget you listen to, but it also means something else. Radio means sending energy with waves. In other words, it's a method of transmitting electrical energy from one place to another without using any kind of direct, wired connection. That's why it's often called wireless. The equipment that sends out a radio wave is known as a transmitter; the radio wave sent by a transmitter whizzes through the air—maybe from one side of the world to the other—and completes its journey when it reaches a second piece of equipment called a receiver.

When you extend the antenna (aerial) on a radio receiver, it snatches some of the electromagnetic energy passing by. Tune the radio into a station and an electronic circuit inside the radio selects only the program you want from all those that are broadcasting.

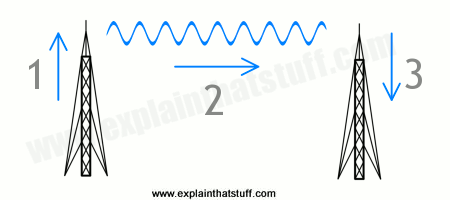

Artwork: How radio waves travel from a transmitter to a receiver. 1) Electrons rush up and down the transmitter, shooting out radio waves. 2) The radio waves travel through the air at the speed of light. 3) When the radio waves hit a receiver, they make electrons vibrate inside it, recreating the original signal. This process can happen between one powerful transmitter and many receivers—which is why thousands or millions of people can pick up the same radio signal at the same time.

How does this happen? The electromagnetic energy, which is a mixture of electricity and magnetism, travels past you in waves like those on the surface of the ocean. These are called radio waves. Like ocean waves, radio waves have a certain speed, length, and frequency. The speed is simply how fast the wave travels between two places. The wavelength is the distance between one crest (wave peak) and the next, while the frequency is the number of waves that arrive each second. Frequency is measured with a unit called hertz, so if seven waves arrive in a second, we call that seven hertz (7 Hz). If you've ever watched ocean waves rolling in to the beach, you'll know they travel with a speed of maybe one meter (three feet) per second or so. The wavelength of ocean waves tends to be tens of meters or feet, and the frequency is about one wave every few seconds.

When your radio sits on a bookshelf trying to catch waves coming into your home, it's a bit like you standing by the beach watching the breakers rolling in. Radio waves are much faster, longer, and more frequent than ocean waves, however. Their wavelength is typically hundreds of meters—so that's the distance between one wave crest and the next. But their frequency can be in the millions of hertz—so millions of these waves arrive each second. If the waves are hundreds of meters long, how can millions of them arrive so often? It's simple. Radio waves travel unbelievably fast—at the speed of light (300,000 km or 186,000 miles per second).

Photo: A radio studio is essentially a soundproof box that converts sounds into high-quality signals that can be broadcast using a transmitter. Credit: Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Analog radio

Ocean waves carry energy by making the water move up and down. In much the same way, radio waves carry energy as an invisible, up-and-down movement of electricity and magnetism. This carries program signals from huge transmitter antennas, which are connected to the radio station, to the smaller antenna on your radio set. A program is transmitted by adding it to a radio wave called a carrier. This process is called modulation. Sometimes a radio program is added to the carrier in such a way that the program signal causes fluctuations in the carrier's frequency. This is called frequency modulation (FM). Another way of sending a radio signal is to make the peaks of the carrier wave bigger or smaller. Since the size of a wave is called its amplitude, this process is known as amplitude modulation (AM). Frequency modulation is how FM radio is broadcast; amplitude modulation is the technique used by AM radio stations.

What's the difference between AM and FM?

An example makes this clearer. Suppose I'm on a rowboat in the ocean pretending to be a radio transmitter and you're on the shore pretending to be a radio receiver. Let's say I want to send a distress signal to you. I could rock the boat up and down quickly in the water to send big waves to you. If there are already waves traveling past my boat, from the distant ocean to the shore, my movements are going to make those existing waves much bigger. In other words, I will be using the waves passing by as a carrier to send my signal and, because I'll be changing the height of the waves, I'll be transmitting my signal by amplitude modulation. Alternatively, instead of moving my boat up and down, I could put my hand in the water and move it quickly back and forth. Now I'll make the waves travel more often—increasing their frequency. So, in this case, my signal will travel to you by frequency modulation.

Sending information by changing the shapes of waves is an example of an analog process. This means the information you are trying to send is represented by a direct physical change (the water moving up and down or back and forth more quickly).

Artwork: Left: In FM radio, signals broadcast at the same amplitude (the waves have the same "height") but their frequency (effectively the period between one wave crest and the next) constantly changes. Right: The opposite is true of AM radio. Here the frequency (period) stays the same but the amplitude (height) of the waves varies.

The trouble with AM and FM is that the program signal becomes part of the wave that carries it. So, if something happens to the wave en-route, part of the signal is likely to get lost. And if it gets lost, there's no way to get it back again. Imagine I'm sending my distress signal from the boat to the shore and a speedboat races in between. The waves it creates will quickly overwhelm the ones I've made and obliterate the message I'm trying to send. That's why analog radios can sound crackly, especially if you're listening in a car. Digital radio can help to solve that problem by sending radio broadcasts in a coded, numeric format so that interference doesn't disrupt the signal in the same way. We'll talk about that in a moment, but first let's see take a peek inside an analog radio.