The Internet

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: May 2, 2023.

When you chat to somebody on the Net or send them an e-mail, do you ever stop to think how many different computers you are using in the process? There's the computer on your own desk, of course, and another one at the other end where the other person is sitting, ready to communicate with you. But in between your two machines, making communication between them possible, there are probably about a dozen other computers bridging the gap. Collectively, all the world's linked-up computers are called the Internet. How do they talk to one another? Let's take a closer look!

Photo: What most of us think of as the Internet—Google, eBay, and all the rest of it—is actually the World Wide Web. The Internet is the underlying telecommunication network that makes the Web possible. If you use broadband, your computer is probably connected to the Internet all the time it's on.

Sponsored links

Contents

What is the Internet?

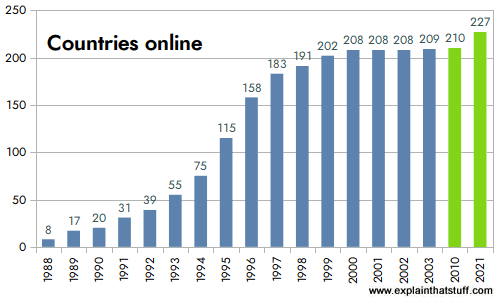

Global communication is easy now thanks to an intricately linked worldwide computer network that we call the Internet. In less than 20 years, the Internet has expanded to link up around 230 different nations. Even some of the world's poorest developing nations are now connected.

Chart: Countries online: In just over a decade, between 1988 and 2000, virtually every country in the world went online. Although most countries are now "wired," that doesn't mean everyone is online in all those countries, as you can see from the next chart, below. Source: Redrawn by Explainthatstuff.com using data from Figure 1.1 "All online, but a big divide", ITU World Telecommunication Development Report: Access Indicators for the Information Society: Summary, 2003, p.5 (blue bars, 1998–2003) and Percentage of Individuals using the Internet 2000–2021 [XLS spreadsheet format], International Telecommunications Union, December 2022 edition (2010 and 2021, green bars). Please note that the horizontal (year) axis is not linear beyond the blue bars.

Lots of people use the word "Internet" to mean going online. Actually, the "Internet" is nothing more than the basic computer network. Think of it like the telephone network or the network of highways that criss-cross the world. Telephones and highways are networks, just like the Internet. The things you say on the telephone and the traffic that travels down roads run on "top" of the basic network. In much the same way, things like the World Wide Web (the information pages we can browse online), instant messaging chat programs, MP3 music downloading, IPTV (TV streamed over the Internet), and file sharing are all things that run on top of the basic computer network that we call the Internet.

Artwork: "Information superhighway": The Internet is like a global road network on which many different kinds of traffic can travel. Much of it seems one way—from distant computers (servers) into your home—but in reality the traffic is always two-way.

The Internet is a collection of standalone computers (and computer networks in companies, schools, and colleges) all loosely linked together, mostly using the telephone network. The connections between the computers are a mixture of old-fashioned copper cables, fiber-optic cables (which send messages in pulses of light), wireless radio connections (which transmit information by radio. waves), and satellite links.

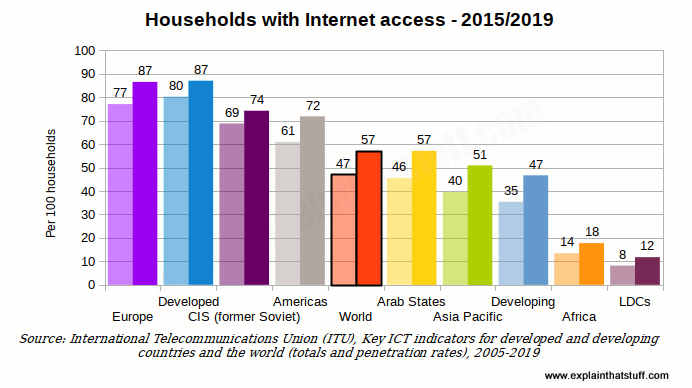

Chart: Internet use around the world: This chart compares the estimated percentage of households with Internet access for different world regions and economic groupings. For each region or grouping, the lighter bar on the left shows the percentage for 2015, while the darker bar shows 2019. Although there have clearly been dramatic improvements in all regions, there are still great disparities between the "richer" nations and the "poorer" ones. The world average, shown by the black-outlined orange center bars, is still only 57 out of 100 (just over half). Not surprisingly, richer nations are well to the left of the average and poorer ones well to the right. Source: Percentage of Individuals using the Internet 2000–2019 [XLS spreadsheet format], International Telecommunications Union, 2020.

What does the Internet do?

The Internet has one very simple job: to move computerized information (known as data) from one place to another. That's it! The machines that make up the Internet treat all the information they handle in exactly the same way. In this respect, the Internet works a bit like the postal service. Letters are simply passed from one place to another, no matter who they are from or what messages they contain. The job of the mail service is to move letters from place to place, not to worry about why people are writing letters in the first place; the same applies to the Internet.

Just like the mail service, the Internet's simplicity means it can handle many different kinds of information helping people to do many different jobs. It's not specialized to handle emails, Web pages, chat messages, or anything else: all information is handled equally and passed on in exactly the same way. Because the Internet is so simply designed, people can easily use it to run new "applications"—new things that run on top of the basic computer network. That's why, when two European inventors developed Skype, a way of making telephone calls over the Net, they just had to write a program that could turn speech into Internet data and back again. No-one had to rebuild the entire Internet to make Skype possible.

Photo: The Internet is really nothing more than a load of wires—metal wires, fiber-optic cables, and "wireless" wires (radio waves ferrying the same sort of data that wires would carry). Much of the Internet's traffic moves along ethernet networking cables like this one.

How does Internet data move?

Circuit switching

Much of the Internet runs on the ordinary public telephone network—but there's a big difference between how a telephone call works and how the Internet carries data. If you ring a friend, your telephone opens a direct connection (or circuit) between your home and theirs. If you had a big map of the worldwide telephone system (and it would be a really big map!), you could theoretically mark a direct line, running along lots of miles of cable, all the way from your phone to the phone in your friend's house. For as long as you're on the phone, that circuit stays permanently open between your two phones. This way of linking phones together is called circuit switching. In the old days, when you made a call, someone sitting at a "switchboard" (literally, a board made of wood with wires and sockets all over it) pulled wires in and out to make a temporary circuits that connected one home to another. Now the circuit switching is done automatically by an electronic telephone exchange.

If you think about it, circuit switching is a really inefficient way to use a network. All the time you're connected to your friend's house, no-one else can get through to either of you by phone. (Imagine being on your computer, typing an email for an hour or more—and no-one being able to email you while you were doing so.) Suppose you talk very slowly on the phone, leave long gaps of silence, or go off to make a cup of coffee. Even though you're not actually sending information down the line, the circuit is still connected—and still blocking other people from using it.

Packet switching

The Internet could, theoretically, work by circuit switching—and some parts of it still do. If you have a traditional "dialup" connection to the Net (where your computer dials a telephone number to reach your Internet service provider in what's effectively an ordinary phone call), you're using circuit switching to go online. You'll know how maddeningly inefficient this can be. No-one can phone you while you're online; you'll be billed for every second you stay on the Net; and your Net connection will work relatively slowly.

Most data moves over the Internet in a completely different way called packet switching. Suppose you send an email to someone in China. Instead of opening up a long and convoluted circuit between your home and China and sending your email down it all in one go, the email is broken up into tiny pieces called packets. Each one is tagged with its ultimate destination and allowed to travel separately. In theory, all the packets could travel by totally different routes. When they reach their ultimate destination, they are reassembled to make an email again.

Packet switching is much more efficient than circuit switching. You don't have to have a permanent connection between the two places that are communicating, for a start, so you're not blocking an entire chunk of the network each time you send a message. Many people can use the network at the same time and since the packets can flow by many different routes, depending on which ones are quietest or busiest, the whole network is used more evenly—which makes for quicker and more efficient communication all round.