TV projectors

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: May 19, 2022.

Everyone knows real life is nothing like television—possibly because TV screens are so much smaller than the things we see around us. You couldn't show life-sized people, cars, sharks, trees, and skyscrapers on a glass-fronted box 30cm (12 inches) high even if you wanted to. But if you'd like your entertainment to feel more realistic, one option is to swap your TV set for a projector that throws giant images of TV pictures onto the wall. Watching TV then becomes more like watching a movie—in the comfort and privacy of your own home. Projection TV is also very useful in business meetings and college lectures where a whole room full of people need to watch a picture at the same time. You can use it to show live TV pictures, video and DVD recordings, or even the output from a computer screen. Let's take a closer look at the different kinds of TV projector and how they work.

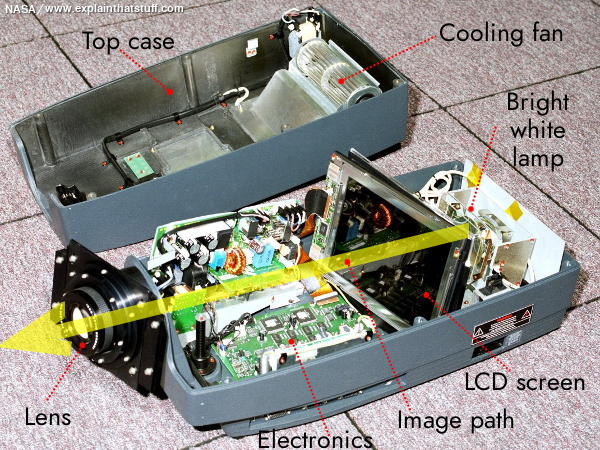

Photo: A typical LCD TV projector with its cover removed. Photo by NASA Langley Research Center (NASA-LaRC) courtesy of Internet Archive.

Sponsored links

Contents

What is projection?

There's nothing new about projecting images onto a screen. Back in ancient times, Greek philosopher Plato (429–347 BCE) described a famous idea called the "allegory of the cave" in which he likened our everyday experiences to those of a group of cave-bound prisoners watching distorted shadows of puppets flickering on a wall. Thanks to Plato, we can say fairly confidently that people have understood the basic idea of projecting simple images onto screens for thousands of years.

Shadow play like Plato described is something all children enjoy and, simple though it is, it's the basis for all forms of projection technology, no matter how sophisticated. Think for a moment how it works. You have a light source, you put an image in front of it, and a shadowy image of the object is thrown onto the wall in front of you. If you move the object around, you create an animated image.

Front projection and back projection

There are two basic kinds of projection. If the light is behind you and the screen is in front of you, you make an image through front projection. You can also make projected images a different way. You might have walked down the street at night and seen shadows of people dancing around on their blinds as they walk around inside brightly hit homes. In this case, the light source and the object being projected are behind the screen (the blinds) and you're looking from the opposite direction in what's known as back projection.

Artwork: In front projection (left), the image is projected in front of you. You see light reflected off the screen into your eyes. In back projection (right), the image is projected through the screen from behind. The light you see is traveling directly through the screen.

"Cine" movie projectors, which were developed in 1895 by two French brothers named Auguste and Louis Lumière (1862–1952 and 1864–1948), work by front projection. The projector is positioned behind the audience and throws an image over their heads onto a screen in front of them. Televisions, which became popular a few decades later, work by back projection. You sit in front of the box and watch a pattern of light that's being created by a very sophisticated electronic mechanism behind the screen.

Photo: The Lumière brothers pioneered the movie projector and opened the world's first cinema in the 1890s.

What is projection TV?

Projection TVs are a cross between the two technologies: they use television technology to build up a picture and projector technology to throw that picture onto the screen. You've probably noticed how televisions have evolved and developed in recent years: huge, old-style cathode-ray tube (CRT) TV sets have gradually given way to flatter, squarer LCD (liquid-crystal display) and plasma TVs that work an entirely different way. Projection TVs have evolved in much the same way.

Artwork: Projection meets TV—a TV projector throws a large TV picture onto your wall instead of squeezing a small one into a screen.

CRT projectors

The first TV projectors were a bit like super-powerful CRT televisions. Although basic CRT TV projectors were available in the 1950s, they became really popular in the 1980s thanks to manufacturers such as Barco. Instead of shining three colored electron guns onto a phosphor screen from behind (that is, by using back projection), they use three hugely powerful light guns to shine separate red, blue, and green images onto a screen (through front projection). The images fuse together into a single, large colored image. The trouble with projectors like this is that they are huge and heavy (so they're not easily portable), they can use lots of electricity (to power the three light guns), and the CRT tubes inside them get very hot. But although they can be fiddly to set up initially and adjust, they're neither unreliable nor obsolete, as many people suppose: they give excellent picture quality (as good as or better than newer technologies) and they're still compatible with new developments like HDTV and Blu-ray DVD players.

Photo: An old-fashioned Barco 801 CRT projector from the early 1990s, with its distinctive blue, green, and red lenses shining out from the front.

LCD projectors

Just as CRT televisions have now largely being replaced by LCD sets, so CRT projectors have gradually gone the same way—and for exactly the same reason: LCD screens are smaller, lighter, cheaper, more reliable, and use much less power than CRTs. In an LCD TV projector, a very bright light shines through a small LCD screen into a lens, which throws a hugely magnified image of the screen onto the wall.

Photo: An ASK Impression 960 LCD TV projector weighing in at about 12.5kg. This one uses a powerful 575-watt metal halide lamp to throw the image of an internal, 25cm (10-inch) LCD screen onto a screen up to 4 meters (13ft) away. Photo by NASA Langley Research Center (NASA-LaRC) courtesy of Internet Archive.

The technology is sometimes called LCLV (liquid crystal light valve). While CRT projectors were popular with businesses and colleges, lower-cost LCD projectors are small, cheap, and portable enough for home use. That doesn't necessarily mean they're superior, however. The image quality is often poorer than that produced by CRT projectors and the bright lamps used inside LCD projectors to throw the image still have a limited life.

Photo: Inside an ASK Impression 960 LCD TV projector, modified by NASA. Photo by courtesy of NASA Langley Research Center (NASA-LaRC) with annotations by Explainthatstuff courtesy of Internet Archive.

Sponsored links

DLP® projectors

Even LCD projectors are looking old-hat now. The latest TV projection technology, DLP® (digital light processing), uses an entirely different method of making images using microscopic mirrors.

Photo: A Christie Mirage 5000: a typical modern DLP TV projector. Photo by courtesy of Dave Pape, published on Flickr under a Creative Commons Licence.

Have you ever used a mirror to send a light signal to a friend some distance away? The basic idea is simple: you angle the mirror so it catches light, then tilt it slightly so the light travels where you want it to go. By tilting the mirror back and forth, you can send precise light pulses of either long or short duration—and transmit complex messages using something like Morse code. The latest projection TV system, called DLP® (digital light processing) technology, works in almost exactly the same way.

What is DLP® technology?

Developed in the mid-1980s by Texas Instruments scientist Dr Larry J. Hornbeck, DLP technology is based on an amazingly clever microchip called a digital micromirror device (DMD). A DMD chip contains about two million tiny mirrors arranged in a square grid. Each mirror is less than one fifth the diameter of a human hair, and it's mounted on a microscopic hinge so it can tilt either one way or another. A bright lamp shines onto the DMD mirror chip and an electronic circuit makes the mirrors tilt back and forth. If a mirror tilts toward the lamp, it catches the light and reflects it off toward the screen, creating a single bright dot of light (equivalent to a pixel of light made by a normal TV); if a mirror tilts away from the light source, it can't catch any light, so it makes a dark pixel on the screen instead. Each mirror is separately controlled by an electronic switch so, working together, the two million mirrors can build up a high-resolution image from two million light or dark dots.

Artwork: DLP® chips make pixels with tiny tilting mirrors. In the original design by Larry Hornbeck, shown here, each pixel is a tiny cloverleaf-shaped plate of aluminum copper alloy (red) that can be electrically attracted by a second plate directly underneath (blue), so it tilts one way or the other on a central hinge (green). Artwork from US Patent 4,710,732: Spatial light modulator and method by Larry Hornbeck, Texas Instruments, 1987, courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

To make color images, DLP projectors need an extra bit of technology: they have a spinning colored wheel inserted into the light path, which can color the pixels red, blue, or green. Combined with the tilting mirrors, the color wheel makes a front-projected TV picture from millions of pixels of every possible color. This is explained more fully in the box below.