Electric doorbells

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: April 1, 2022.

Ding dong! Sometimes we love that sound, sometimes we hate it. But if there's one thing I love it's the science behind it. When someone's finger pushes on my doorbell, what I can hear is the sound of impressively simple 19th-century physics—the science of electromagnetism, to be exact. Just what happens when the doorbell goes "ding"? Let's take a closer look!

Photo: A simple "push-to-make" switch activates the doorbell's electric circuit when you push it in. When you release it, a spring makes it pop out and it breaks the circuit again.

Sponsored links

Contents

How does an electric doorbell work?

When I was about eight or nine, I built a very crude doorbell for my bedroom. It was a simple electric circuit containing a battery, a switch, and an electric motor standing on a large cardboard box. When a caller pressed the switch, the battery fed power to the motor and made it spin around with a buzzing noise (a bit like the vibrating alert on a cellphone or pager). Standing on the box, the motor made a reasonably audible but rather dull humming noise.

Real electric doorbells aren't that different. Instead of using an electric motor and a cardboard box, they use an electromagnet (a temporary magnet whose magnetism can be turned on and off instantly by electricity) to make a more attractive sound, either with an electric bell, a buzzer, or chime bars struck by a magnetic hammer. Like my toy bell, many household doorbells are powered by batteries; others draw small amounts of power from the household electricity supply with the help of a transformer.

Photo: A piezoelectric buzzer makes a chirping noise—the "ring tone" in modern landline telephones. Although cheaper doorbells do sometimes contain buzzers like these, most have more sophisticated ringers.

Clapper doorbells

Most doorbells have what's called a "push-to-make" switch outside your door, like the one in our top photo. When you prod the button, your finger pushes two electric contacts together to complete ("make") the circuit; when you release the pressure, a spring moves the button back out again so the circuit is interrupted.

Animation: How a doorbell clapper works as part of a self-interrupting circuit. For the sake of simplicity, this picture doesn't include the electromagnet and the battery (which are wired into the circuit) or the spring that pulls the clapper back to its original position; those are shown in the next picture.

Like my own primitive doorbell, the circuit itself contains only two basic elements: a battery and something that makes a noise. The "something" is often an electric bell: a little metal bell (like one on a bicycle) and a clapper (hammer) powered by an electromagnet. When someone presses the button, the electromagnet is activated and pulls on the clapper, which strikes the bell. But here's the clever bit: the clapper is actually also part of the circuit. When it flips out to strike the bell, it breaks the circuit at the same time, cutting the power to the electromagnet. A spring attached to the clapper pulls it back to its original position, whereupon it completes the circuit, energizes the electromagnet, and rings the bell once more. This goes on for as long as you keep the button pressed. Or until the batteries run out!

Artwork: Inside a clapper doorbell. Press the button (red) and the electromagnets (green) attract the clapper (yellow). As the clapper moves in, it breaks the circuit and its mounting spring lets it spring back out again. The process repeats until you let go off the button. Artwork from US Patent 592,269: Electric vibrating bell by Henry F. Albright, courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

Push-to-make switches can be used to make more sophisticated doorbells. The one below, dating from the early 20th century, uses two interlinked push-to-make circuits. The first one, shown in red, connects a pressure switch (green, 12), battery (10), and lamp (yellow, 21). The switch is placed under a doormat so it closes, operates the circuit, and lights the lamp whenever someone approaches the house. The lamp is meant to be placed right next to the push-button doorbell switch (44)—perhaps even to shine right through it—so it indicates what the caller should press when he or she arrives in the dark. When the switch (44) is pressed, it breaks the red circuit and operates the blue one instead. Now power from the batteries energizes the electromagnet (pink, 15), bringing the bell clapper (green, 14) repeatedly in contact with the bell itself (orange, 16).

Artwork: From US Patent: 769,203: Electric Signal by William Wheeler, patented September 6, 1904, courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

Chime doorbells

Ding-dong chime doorbells are slightly more sophisticated. They have two metal bars at either side that make the two different musical notes when something hits them. In between are mounted batteries and an electromagnet with a freely moving "hammer" inside it—essentially just a cylinder of magnetic metal that slides back and forth inside a slightly bigger cylindrical plastic tube. When you press the doorbell, the electromagnet magnetizes the metal hammer and pulls it way to the right, compressing it against a spring and striking the metal chime bar on the right: ding! At this point, the circuit is interrupted and the electromagnet switches off, so the spring makes the hammer shoot back the other way, striking the metal chime bar on the left: dong! The chime bars are very lightly mounted on plastic fasteners so they vibrate for a few seconds before the sound dissipates.

Photo: Inside a chime doorbell. The chime bars are on the right and left. The electromagnet and the moving hammer are in the black plastic box in the center.

Wireless doorbells

There's one big problem with conventional doorbells: if you have a large house (or you're often outdoors in a garden or yard), you may not hear them ringing. One solution to that is to have a wireless doorbell, which has a conventional push switch mounted on the outside of your door and a battery-powered ringer unit you can carry from room to room (or outdoors, if you wish). The switch contains a miniature, short-range radio transmitter that can send a signal (433 MHz is typical) up to about 100 meters (300 ft or so) to the radio receiver in the ringer unit. Most wireless doorbells allow you to select different radio channels, so you can use several different ones in one building without them interfering—and ensure your doorbell doesn't ring when someone arrives at a neighbor's house!

Doorbells for apartment blocks

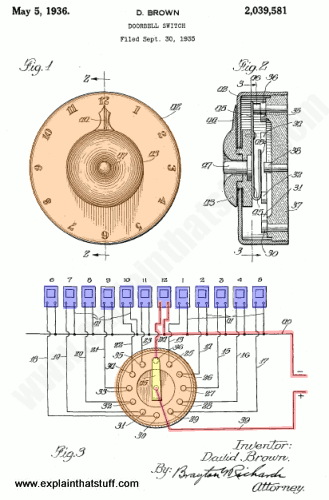

Head to the front door of an apartment block and you'll likely find a whole set of doorbells, one for each household. It's not the most elegant bit of electrical engineering, but it works. Go to an older building and, if you're very lucky, you just might come across an elegant, antique, rotary doorbell like the one shown here. As with the doorbells described up above, this one is designed to activate a simple electrical circuit that rings a bell inside someone's home; you simply turn the dial to point to the apartment number you want then press the button in the center. What's clever about this bell is the rotary switch on the dial, which allows the doorbell to activate one of 12 separate circuits, each running to the bell inside a different apartment. How does it work? As you can see in the lower part of the diagram, the dial pointer is a key part of the circuit. When it turns to one of the apartment numbers, it completes the circuit for that apartment only.

Photo: How a rotary doorbell switch works. This design is by David Brown, an inventor from Chicago, and dates from 1935. In the lower figure, I've colored (in red) the circuit for apartment 12, showing how the doorbell pointer completes the circuit for that apartment when it points straight upward. Read more about this invention in US Patent: 2039581: Doorbell Switch. Drawing courtesy of US Patent and Trademark Office.

How do electric door entry systems work?

If you live on one of the upper floors of a modern apartment block, you probably have an electric door entry intercom or videophone, allowing you to let people into your building without having to trudge all the way down the stairs and back again. Systems like this don't have much in common with traditional electric doorbells. Typically, they use an intercom that links a combined microphone and loudspeaker grille on the front door of the building to a separate telephone-style handset in each apartment. Each handset has an extra button on it that links back to the latch on the front door. When you press the button, it triggers a relay, which energizes a solenoid (a type of electromagnet) that pulls back the latch on the door, letting people in.

About the author

Chris Woodford is the author and editor of dozens of science and technology books for adults and children, including DK's worldwide bestselling Cool Stuff series and Atoms Under the Floorboards, which won the American Institute of Physics Science Writing award in 2016. You can hire him to write books, articles, scripts, corporate copy, and more via his website chriswoodford.com.