Gravity

by Chris Woodford. Last updated: January 6, 2022.

What goes up, must come down. That's one way of looking at the weird phenomenon we call gravity, but it's far from the whole story. Some things—space probes and satellites spinning over our heads—never come down. And the idea of gravity as a simple up-down force happening purely on Earth is very wrong too.

Gravity is like invisible elastic stretched through the whole universe, holding the stars and planets together and pulling them toward one another. Much more significantly, it's a fundamental force between every bit of matter in the universe and every other bit: just like Earth and the Sun, you have your own gravity, and so do I. From Aristotle to Kepler and from Newton to Einstein, understanding gravity has challenged some of the best scientific minds in history. Thanks to their efforts in getting a grip on this tricky topic, we can do all kinds of neat things, from figuring out where we are with GPS satellites to making sure bullets hit the spot. But that still leaves an important question: just what is this thing we call gravity and how does it work? Let's take a closer look!

Photo: Gravity in all its beauty! Gravity's pull varies from place to place, both on Earth and elsewhere. This is a map showing how the strength of gravity varies across the Mare Orientale on the moon. Image courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Sponsored links

Listen instead... or scroll to keep reading

Contents

What is gravity?

Gravity is a pulling force (always a force of attraction) between every object in the universe (every bit of matter, everything that has some mass) and every other object. It's a bit like an invisible magnetic pull, but there's no magnetism involved. Some people like to call this force gravitation and reserve the word gravity for the special kind of gravitation ("what goes up must come down") that we experience here on Earth. To my mind, that's unnecessary and wrong, and I'll explain why when we talk about Isaac Newton in a moment. In this article, I'm going to use the word gravity for everything (both gravity and gravitation).

If you've heard physicists talk about the four fundamental forces (or four fundamental interactions) that control everything that happens around us, you'll know that gravity is one of them—along with the electromagnetic force and the two nuclear forces that work on very small scales inside atoms (known as the strong and weak forces). Gravity is very different from these other forces, however. Most of us can remember playing with magnets in school and one of the first things you learn by doing that is that two magnets can attract or repel. Gravity can certainly attract, but it never repels. While magnetism can be an incredibly strong force over very short distances, gravity is generally a much weaker force, though it works over infinitely long distances. The gravity exerted by your body, right now, is pulling the Sun toward you—just a tiny bit—across a distance of something like 150 million kilometers!

Artwork: Gravity keeps the planets in orbit around the Sun, even at immense, astronomical distances. Spacecraft, like Mariner 10 shown here, sometimes use what's called a "gravity assist" to help them achieve a new orbit or a different velocity. Artwork courtesy of NASA

Gravity on Earth

Cars, trucks, airplanes, mosquitos, your body and everything around you—it's all stuck to Earth by the force of gravity. If we've just said gravity is a weak force, how is that possible? How can such a weak force pull something like a huge Jumbo jet down toward the ground?

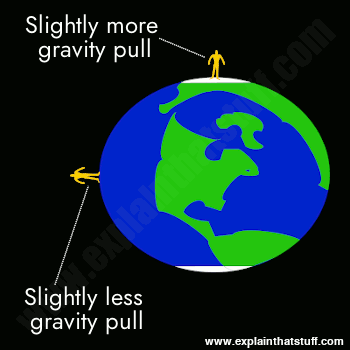

Gravity might be weak, but Earth has a lot of it because our planet is so big and we're relatively close to it (compared to our distance from the Sun, anyway). Often it helps to think of Earth's gravity originating at a single point at the center of the planet's core. The amount of gravity you feel at any place on Earth depends how far you are from this point, so it's slightly more at sea level and slightly less when you're up a mountain. Now Earth isn't a perfect sphere: technically, it's what's called an oblate spheroid—it's flattened at the poles and bulges at the equator. That means gravity also lessens with latitude (it's slightly less at the equator than at the poles). Finally, because Earth is spinning around, and people at the poles are moving less quickly (relative to space) than those at the equator, that also slightly reduces the effects of gravity. Add all these things together and you get a variation in gravity between the equator and the poles of much less than 1 percent, so for most everyday purposes, we can say that gravity at sea level is the same right across Earth. [1]

Artwork: The force of gravity is slightly lower at the equator than at the poles. Please note that this figure is not drawn to scale and Earth's bulge is hugely exaggerated!

Why might it matter that gravity varies on Earth? First, and perhaps least importantly, it affects how much you weigh. If gravity is more at sea level, you weigh more there! The quickest way to lose weight is to climb an especially high mountain—not because all the effort makes you lose any body mass, but because the force of gravity is weaker the further you go from the center of the Earth. Second, gravity pulls everything toward Earth (the invisible, gassy atmosphere around us as well as everything else), and that's why we have air pressure (on land) and water pressure (in the oceans). These things vary with altitude (above Earth's surface) and depth (below sea level).

If gravity is a force tugging us toward a point in the center of the planet, why don't we keep on being pulled in? Why doesn't gravity tug you through the floor of your house and the rocks below to suffer a really rather unpleasant death in the heart of Earth's fiery core, deep beneath your feet? If you're sitting still in a chair right now, it means all the forces on your body are balanced. So the downward pull of gravity must be balanced exactly by another, upward-pushing force. As gravity tries to pull you down, the atoms in the chair push back upward—you can't squash atoms that easily—and counteract with what is essentially an electromagnetic force. When someone stands on the floor and goes nowhere, the ground is effectively pushing back up again and saying "I will not be squashed." We call the upward-pushing force from the ground that balances downward-pulling gravity the normal force.

Gravity in space

Photo: Astronauts train for space in a "vomit comet": It simulates weightlessness by making deep dives toward Earth. Photo courtesy of NASA on The Commons.

Scientists used to think Earth sat at the center of the Universe: theories of astronomy were geocentric, which means Earth-centered. Until the 16th century, most people thought the Sun rotated around Earth, rather than (as we now know) the other way around. There was tremendous religious opposition to the idea that Earth spun around the Sun, which is called the helicentric (Sun-centered theory). That idea was first put forward by the ancient Greek thinker Aristarchus (c.310–250 BCE), revived by Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), and championed by Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). When it comes to gravity, we now accept that Earth isn't at the center of things: it isn't special and it's no different from anywhere else. That's one reason why it makes no sense to talk about gravity (Earth's "special" gravitation) and gravitation (other kinds of gravitation, in other situations or elsewhere). But you'll still see both of those two words used widely. (Isaac Newton formulated a law of "gravitation," as we'll discover in a moment.)

Photo: Galileo Galilei, an Italian astronomer, investigated how gravity accelerates things on Earth and championed the idea that Earth orbits the Sun. Picture from Carol M. Highsmith's America Project in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, courtesy of US Library of Congress

Just like Earth, every planet (or moon) has a different amount of gravity; bigger planets (or moons) have more gravity than smaller ones. So our own Moon has gravity, but it's about one sixth as much as Earth's (because the Moon has less mass and it's much smaller). That's why astronauts weigh one sixth as much on the Moon and why they can jump about four times higher in the air when they're there. Jupiter has gravity too and because it's bigger and more massive than Earth, you'd weigh almost three times more there and struggle to jump very far at all.

Gravity also explains why the universe looks and behaves the way it does. If you've ever wondered why planets are nice round shapes (roughly spherical) and not square boxes, gravity is the answer. When the planets were busily forming from fizzing atoms and swirling atomic dust billions of years ago, gravity was the force that tugged them together. If lots of matter is pulled toward a central point from many different directions, a sphere is what you end up with—just like you end up with a snow ball if you pat snow together hard from all sides. Invisible "strings" of gravity also explain why the planets dance around one another in the strange cosmic patterns we call orbits. Although we often think of orbits as circular, they're actually ellipses, which are stretched-out, oval relatives of circles (a circle is a special kind of ellipse).

“... one of the theories proposed was that the planets went around because behind them were invisible angels, beating their wings and driving the planets forward. You will see that this theory is now modified!”

Richard Feynman, Six Easy Pieces

How does gravity work?

Early scientific ideas about gravity were based on watching how things naturally fell toward the ground. Aristotle, the ancient Greek philosopher, who lived about 2350 years ago, famously believed that heavier things fall faster than light ones, so if you drop a stone and a feather at the same time, the stone wins the race and hits the ground first.

Meanwhile, the whole question of how planets moved in space was considered an entirely different matter. In Aristotle's mind, Sun, moon, planets, and stars all marched in circular orbits round Earth. Astronomers such as Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus, 100–170 CE) built on this model, but didn't really connect motion in space with what was happening back on Earth. Like Aristotle, Ptolemy was confident that the Sun and planets spun in circles round Earth. Even though his ideas were wrong, his book of astronomy, The Almagest, was accepted as scientific truth for over 1400 years (until Nicolaus Copernicus came along) because no-one else had any better ideas. "Almagest" actually means "The Greatest": Ptolemy's really was the greatest scientific explanation of the world people had at that time.

Artwork: Before people understood gravity, they had to devise ingenious explanations for why the planets moved. In this 14th-century illuminated manuscript, angels make the planets rotate by cranking giant handles! For more about the development of these ideas, see the fascinating Wikipedia article Dynamics of the celestial spheres. Illustration attributed to the atelier of the Catalan Master of St Mark, Spain, 14th century, courtesy of the British Library and Wikimedia Commons.

Aristotle was correct in one sense (a stone beats a feather in a race to the ground), but we now know that everything falls at exactly the same rate and the feather only loses because air resistance (drag) pushes up against it, slowing it down. The person who figured this out, toward the end of the 16th century, was Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei (1564–1642). According to some historians, Galileo experimented with metal balls on a tilted ramp, quickly concluding that the force of gravity accelerates every object—feathers just like stones—at exactly the same rate, which we now call the acceleration due to gravity (or g). Other science historians claim Galileo figured out his ideas by dropping balls from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, while a third theory is that all these were "thought experiments" that he carried out in his own mind. Either way, we now know that all masses are accelerated in the same way; for most practical purposes, g is a constant value everywhere on Earth (although, as we saw up above, it does vary slightly due to altitude, latitude, and so on).

Photo: Isaac Newton—the man behind our modern understanding of gravity. Picture courtesy of US Library of Congress.

While Galileo was musing over gravity on Earth, other astronomers had been coming up with more detailed accounts of how planets moved in space. Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) and Galileo advanced the idea that Earth moved around the Sun. The German Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) believed this too—and realized exactly how it might work. He took a treasure trove of very accurate and detailed observations compiled by another astronomer, Tycho Brahe (1546–1601), and used it to figure out three deceptively simple mathematical laws that seemed to sum everything up. Kepler realized that the planets move in ellipses around the Sun, not circles as had long been supposed. He found that they "sweep out equal areas in equal times," which essentially means they move faster when they're nearer the Sun and slower when they're further out—but in a very predictable way. Finally, he showed how the size of a planet's orbit was related to the time it took for the planet to make a complete circuit around the Sun. It's pretty obvious that if a planet has a bigger orbit, it will take longer to go around it, but Kepler figured out the precise relationship between the two things. (Specifically, he showed that the time a planet takes to orbit, squared, is proportional to its distance from the Sun, cubed.)

But the real stroke of genius in understanding gravity came from English scientist Isaac Newton (1642–1727). He realized that the force of gravity that makes things fall to Earth is exactly the same as the force of gravitation that keeps the planets spinning around in space, which is why I prefer to use the same word for both phenomena. According to the popular myth, Newton figured this out when he saw an apple falling in his garden. Whether that really happened, no-one knows—but it was an incredibly impressive insight that changed science forever. Building on Kepler's work, Newton calculated that a falling apple experienced the same gravity as the Moon would experience being pulled toward Earth. That led him to his groundbreaking law of universal gravitation, published in 1687.

Artwork: Three men who revolutionized astronomy: Copernicus (left), Galileo (right), and Kepler (far right) developed our modern view of the universe with the Sun at its center. Illustration by W. Marshall from a book cover c.1640, about a decade after Kepler's death. Artwork courtesy of US Library of Congress.